ut of the box. Thinking, getting, being “out of the box” is a well-worn cliché. I’ve used it, and you probably have, too. But what is this box we’re all talking about? What’s in it, what keeps us in it, and why do we want so badly to get out of it?

These are the questions I thought about on the train from New York to New Haven a couple years ago to teach a group of executives about innovation strategy at Yale’s School of Organization and Management. I was curious how to make these questions more real and relevant. So I decided to try an experiment.

Photo by Jim Block

Photo by Jim Block

ut of the box. Thinking, getting, being “out of the box” is a well-worn cliché. I’ve used it, and you probably have, too. But what is this box we’re all talking about? What’s in it, what keeps us in it, and why do we want so badly to get out of it?

These are the questions I thought about on the train from New York to New Haven a couple years ago to teach a group of executives about innovation strategy at Yale’s School of Organization and Management. I was curious how to make these questions more real and relevant. So I decided to try an experiment.

When I arrived, I asked my Uber driver to take me to a pizza parlor. “Which one?” he asked (New Haven is famous for pizza). I suggested he pick his favorite, and that led us to Yorkside Pizza. I walked in and asked for the manager. Out came George Koutroumanis, who introduced himself and asked what I needed. “I need 40 pizza boxes and I’m not going to buy a pizza right now,” I replied.

He laughed and asked, “What do you want them for?”

I explained my idea. I wanted to make the “out of the box” cliché a real experience, and I thought pizza boxes might be an appropriate way to do that for a group of professionals studying at Yale. George laughed again, said he liked the idea, and asked his staff to bring me the boxes. When I offered to pay him, he refused, merely asking that I let the class know where they could get a great pizza while they were in town. I, of course, agreed to his generous offer, and left with my boxes.

The next day, when I asked the executives if they used the “out of the box” saying, everyone’s hand went up. I then asked them to think more specifically about what they felt were the primary factors that actually kept them, their teams, or their organizations inside that proverbial box. As they pondered that question, I passed out the unassembled pizza boxes and suggested they write their answers on the inside walls of George’s boxes.

They then compared notes with their neighbors. Here are some of their answers:

- “We’re afraid [of failure, the unknown, taking the first step, being punished if we’re wrong, etc.]”

- “Nobody ever asked me/us to get out of the box”

- “We don’t have enough [time, money, information, talent, etc.]”

- “We spend too much time following procedures and protocols”

- “We don’t have the authority to make changes in our company”

A quick 5-minute experiment for you:

How would you answer

the same question:

“What keeps you, your team or your organization ‘inside the box’?”

If you have a box handy, great. If not, why not just draw one like this?

- “We’re not sure we really need to change”

- “We don’t have a clear idea of what and where we need to change”

- “We don’t understand how our customers’ expectations have shifted”

After this first exercise, I invited everyone to assemble their boxes (not as easy as it might seem, unless you’re in the pizza business). Since this first round went so well, I decided to go for a second. This time I asked them to close their eyes for a minute and just imagine what might lie outside the box they had just created:

What might your organization, your team or you personally be able to do? What would the outside look or feel like? Are there any organizations or experiences that resemble your sense of those possibilities? If an observer saw your activities outside the box, what words might she or he use? What metaphors or visual images capture the essence of your work or organization’s culture outside?

These questions worked, too. Everyone wrote their answers on the outside panels of the pizza boxes, and then we compared notes.

One of the most surprising things about this second sequence was the emotional content of the words many used: fun, joy, happy, proud, free, unafraid to try things, engaged, eager, inspired, etc. And look at the work- and culture-related descriptions they often cited: collaborative, innovative, committed, supportive, exemplary, confident, shaping our future, etc.

In short, their descriptions of the possibilities outside the box expressed the inverse of much of their experienced reality inside, and also captured the essence of what many leaders and executives strive for in their organizations – namely, getting unstuck from the boxes they’re in.

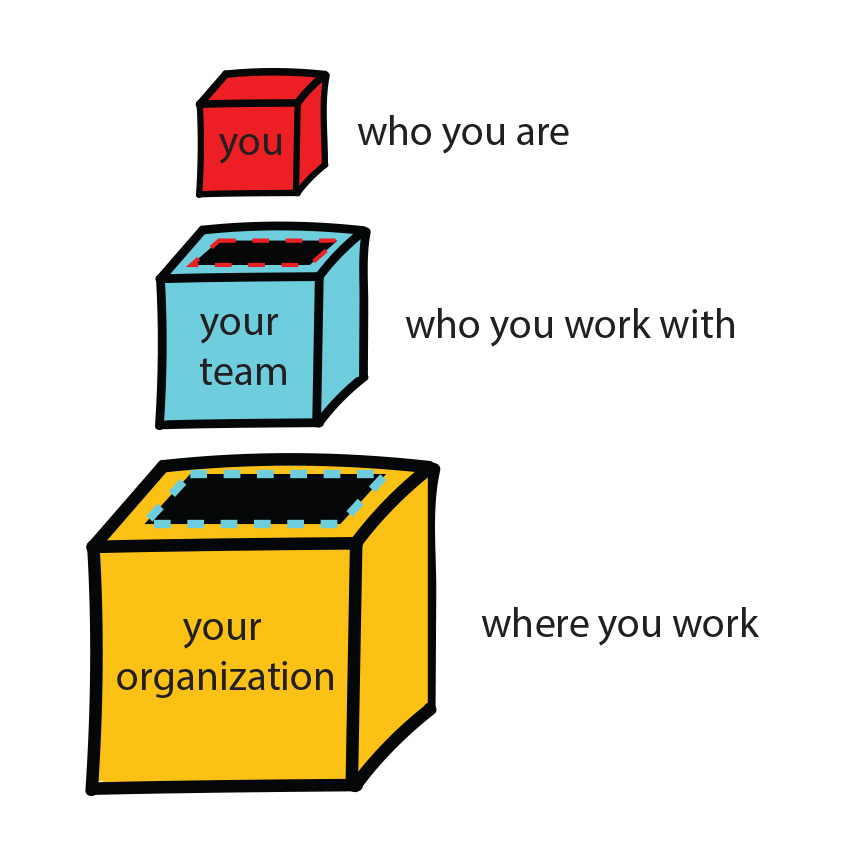

Everybody lives, works, and even thinks inside boxes. I do, you do, our teams do. So do our organizations.

Lots of boxes! Physical boxes like rooms, offices, cubicles, houses, apartments and cars. Work boxes like departments, titles, layers, procedures and job descriptions. Conceptual boxes shaped by our senses, perceptions, assumptions, stereotypes, biases and mental models. Emotional boxes formed by our fears, feelings and expectations. And cultural boxes framed by our history, upbringing, identity and norms.

Those boxes can be very useful. They contain things, organize things and store things. They can also define and protect things. That’s great.

But they can also constrain things – like ideas, creativity, innovation, understanding, hopes, dreams and change. That’s not so great, especially when the way things are isn’t so great to begin with.

Since that original pizza box trial run, I’ve done this exercise with dozens of groups and thousands of people around the world, from corporate executives and government policymakers to my students at UC Berkeley and Princeton. That experience has led me to an even more basic insight: All of us are involved in some form of a “from . . . to” journey – trying to improve our organizational, professional and/or personal reality from today to tomorrow.

But we all face one major barrier in that journey. What keeps so many of us and our organizations from making that “from . . .to” journey successfully? What gets in our way?

We humans have faced many kinds of barriers – the sound barrier, the four-minute mile, glass ceilings, racial and other forms of discrimination, and the like. Many have yielded to new technologies, new ways of thinking, and new leadership values. But what about the barrier that stands between “what is” and “what might be”? What is it?

I think it deserves a name, so I’ve nicknamed it the “NOW Barrier.” The fancier name for this barrier is the STATUS QUO. It’s the biggest obstacle, and the craftiest competitor we face as leaders regardless of the setting in which we work, where we live, or the role we play. If you want to see it face-to-face, just look inside that metaphorical box. That’s where the status quo lives . . . every day.

The status quo is a powerful force, and it’s one that usually has our own fingerprints all over it. Because despite our words, even our hopes about wanting change, our actions suggest most of us may actually prefer what is to what might be.

Consider the walls of those organizational, team, or personal boxes we spend so much time in. Having now led this box experiment-turned-exercise in many different cultures and professional arenas, I’ve come to appreciate the particular power of these six walls:

- Fear of failure. While many organizations and teams talk about the importance of trial-and-error innovation, far too many people inside experience cultures that feel more like trial and terror.

- Scarcity. Most of us operate most of the time in conditions of scarcity – not enough time, money, facts, people, etc. The key question is whether that reality becomes an excuse for inaction, or simply a recognition of everyday constraints that can be the impetus, if not the inspiration, for ingenuity and creativity both inside and outside the box.

- Complacency. Individuals, teams and organizations too often settle into a comfort zone, even when they are falling behind in their fields of endeavor. Without a felt need or desire to change, we see what is as what was meant to be, and that sense reinforces and rationalizes the status quo itself.

Photo by Jim Block

Photo courtesy of John Danner

- Self-Identity. This works two ways. On the one hand, some people seem to simply not expect much of themselves or their work, so the box stays put – with a low ceiling. But many others have higher expectations, for themselves and/or their organizations. They’re less likely to settle for less, and that wall of self-identity becomes more of a floor than a ceiling or limit on their own aspirations.

- Hubris. This one’s tough. First, because it’s just over the line from the kind of self-confidence most leaders want in their organizations. So it’s a close cousin to something usually positive. But second, it’s often hard for organizations, teams and individuals to recognize their own arrogance; hence, this wall may not even be visible to them.

- Ignorance. Sometimes people stay in the box because they don’t know either what’s happening outside it or what to do about it if they do know. Curiosity yields to conformity, reinforcing the other walls of complacency and arrogance.

Any one of these is strong on its own, as you can probably attest if you’ve ever tried to move one, much less break through it. But the underlying secret is that all these walls are quite vulnerable. Maybe not as vulnerable as France’s infamous Maginot Line in World War II or the four-minute mile barrier, but vulnerable nonetheless . . . IF you recognize their inherent weakness.

Walls hate questions. Questions open possibilities; boxes don’t.

Most walls, even ones that at first seem objectively real and powerful, rest on a foundation of assumptions, assertions, authority or beliefs. Questions challenge all four of these foundations, and the complacency or obedience they tend to produce. And those foundations are only as strong as the facts, wisdom or power on which they are based.

Questions can be scary. They can invite and incite. But they are, by definition, the gateway to true learning, as opposed to mindless obedience or going through the motions. Questions demonstrate humility and fallibility (“I don’t have all the answers”), courage (“what makes you think so?”), or just plain pluck (“why can’t we do x, y, or z?”).

Maybe most importantly, questions express curiosity about what is as yet unknown, whether you decide to improve inside the box you’re in or try to get out of it.

Questions alone will not – unlike the gospel song about Joshua’s trumpets at the walls of Jericho – cause your walls to come “tumblin’ down” all by themselves. But the answers to them will make you wiser about which walls you can dismantle and which walls you can work around or with.

Try these six deceptively simple questions to start. They can act like Kryponite on the six walls and the people who erect and defend them:

- Why is this issue of importance to us and our unique mission?

- Where do we need or want to go?

- When do we need to arrive at that destination?

- What if we looked at this issue differently?

- Why not try something different this time, unless we have proof that what we’re already doing is getting us where we need to be?

- Who is best able to understand, address or lead this issue, regardless of where they are or what they do now in our organization?

That’s how you and your team might get started thinking and getting out of that box you may be stuck in today. You might even order in some pizza to get things going. Good luck!