t’s mid-morning. It’s dry, dusty, hot and almost 100° F. I’m walking through the market in Old Fangak, South Sudan. This is the equivalent of your local shopping mall, yet it’s unlike anything you’d find in my hometown of Anchorage, Alaska, or probably in your hometown either.

There are more than 100 small shops. Most are bamboo-walled with roofing made of tarps. Some are simply out in the open under the sun. “I love Africa,” Air-Jordan and Gucci logo shirts blow in the wind, along with pink bras, blue sneakers and long, multi-colored dresses similar to the Indian sari. You can also buy candy, bags of sorghum and barbecued goat.

The market is busy, noisy and vibrant. Nothing like what I experienced on my last visit seven years ago, when the market had just a couple dozen shops and almost no goods. The difference? Clean water, health care and war.

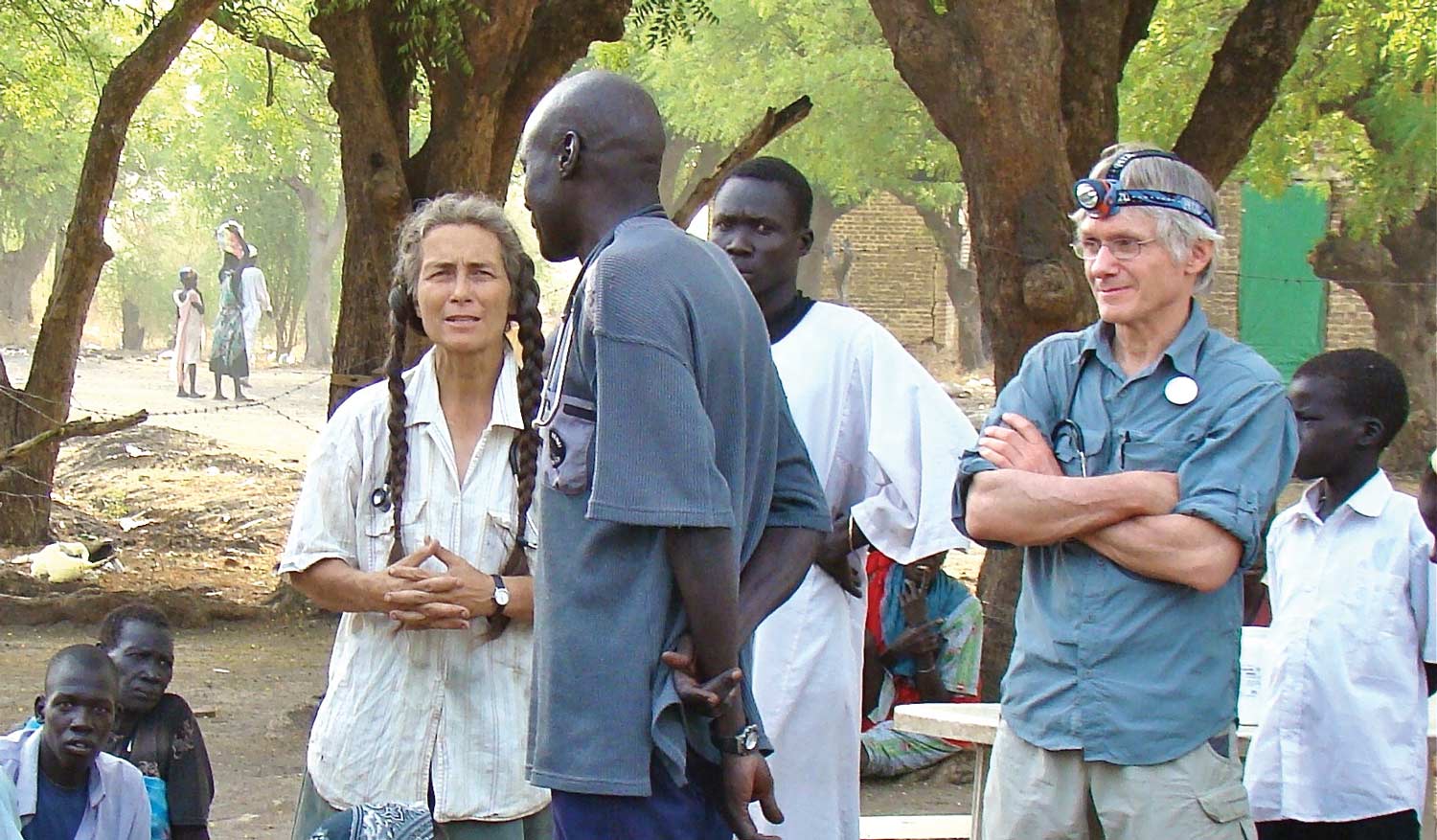

In 2013, civil war erupted in South Sudan. Like a wildfire in a wind storm, it spread quickly and destroyed villages in its path. In this part of South Sudan there was one safe haven, one village that war would not touch: Old Fangak, along the Zaref river. Old Fangak is in a remote, roadless area where the Alaska Sudan Medical Project has since built a medical clinic and drilled more than a dozen bore holes for clean water. Today, Old Fangak, a village of 5,000, is home to at least 50,000 refugees.

As I’m walking today, a woman stops me. We face each other. She looks old, but I can’t guess her real age. Life is hard here, especially for women who do most of the household labor. As I wonder what she wants, she points to her feet, bare and tough as leather. The ground is hot, cracked and riddled with thorns. She needs sandals.

I’m typically not one who likes to bargain. Perhaps it’s being a middle child, often the problem solver, quick to find compromise. But today I decide to be a tough negotiator. He wants $5. I offer $2. The sandals are already on her feet. Eventually we meet at $2.50. I go on my way and she does too.

As I walk through the site, there are 30 or more men, women and children gathered for their daily tuberculosis treatment. This is a new health crisis. The influx of refugees has brought more tuberculosis and TB patients with HIV. Dr. Jill estimates she’ll treat 250 TB patients this year in Old Fangak. Like the woman who needed sandals for her feet, the sick need a place to receive proper treatment. And like the woman in the market, these tuberculosis patients cannot accomplish this without help.

It might not be as easy as bargaining for a pair of sandals. But I know that as part of the Alaska Team, together we’ll get it done. We understand the need. We know the end result we are seeking. Now it’s a matter of taking all we have learned in the last decade and putting it to work.

The Alaska Sudan Medical Project is really about hope. Hope and health for life in South Sudan, for life everywhere. On this day I saw this clearly in the face of a woman with a new pair of sandals. I heard it in the voices of men singing beneath the trees. I felt it in my heart. It’s been a good day.

Todd Hardesty is an Emmy award-winning filmmaker and owner of Alaska Video Postcards, Inc., an Alaska-based film production company. He began his work with the Alaska Sudan Medical Project first as a volunteer, then as a board member. In 2018, Hardesty was named Executive Director of the Alaska Sudan Medical Project. His film about the Alaska Team in Old Fangak called “The Village” has been viewed on YouTube more than 1.6 million times.

Todd Hardesty is an Emmy award-winning filmmaker and owner of Alaska Video Postcards, Inc., an Alaska-based film production company. He began his work with the Alaska Sudan Medical Project first as a volunteer, then as a board member. In 2018, Hardesty was named Executive Director of the Alaska Sudan Medical Project. His film about the Alaska Team in Old Fangak called “The Village” has been viewed on YouTube more than 1.6 million times.