Focusing on Primary Education

Why We Need a Revolution for How We Treat Our Very Young

By Dr. Amir Ullah Khan, PhD

The silence

What is our biggest development challenge today? This is my favorite question to ask my economic policy class, one that I teach around the world to various age groups in different cultural settings. The answers I hear include the various problems the world is facing today: poor quality healthcare, falling standards in education, malnutrition and obesity, global warming, climate change, energy security, terrorism, migration, corruption, governance, trade wars, geopolitics, and increasing sub-nationalist tendencies. This list could go on and cover most issues facing both the developed and the developing world.

What surprises me is that almost never does anyone mention what I have begun to realize is our greatest developmental challenge today: how poorly we treat our women. The data we have is mind-blowing. The tragedy is that it is still not enough for most of us to sit up and take notice. Crime against women is what occupies headlines these days. But from sexual harassment at work to widespread rape, the wanton abuse of our womenfolk continues regardless. From the United States, where the MeToo movement is in full force, to the country of India where I live and work, in which the challenge is particularly severe, it’s a worldwide problem.

Twelve million brides below the age of 10. Falling female work population rates, even in sectors like information technology and software that are considered female-friendly and accessible. Despite all this, there is an inexplicable unwillingness to acknowledge the problem. We either deliberately ignore the issue or are unwittingly caught in a popular narrative of progress that does not allow a questioning of the status quo. And that, to put it simply, is the biggest impediment to innovation: the unwillingness to tackle problems and find solutions.

Analyzing the problem

Women have poor access to infrastructure. Digital empowerment is a major buzzword, but less than 40 percent of women have access to the internet. A large number are denied modern healthcare. More than half of our pregnant mothers suffer from anemia and low iron counts. Topping it all are severe social impediments to advancement: The pressure on women to get married, produce and rear children, and perform household chores denies most women the opportunities that exist elsewhere.

These many problems can seem insurmountable. But very often innovation is preceded by identifying the weak links, the creaky parts, and the problem areas. Let us therefore focus on one pivotal problem: Lack of access to quality primary education prevents advancement, mobility, and a healthy life. Most of our daughters who are enrolled in schools drop out as they find it difficult to cope. Sometimes they must return home and look after younger siblings. Sometimes the reason for dropping out is the absence of basic toilet facilities in schools. Often it is because the school is far away and the walk is not safe. But very often, it is because school is an unfriendly, tedious, and painful experience. Teachers are absent, pedagogy is archaic, and learning is impossible.

Simple solutions, small innovative steps

A few of us got together to see how we could help improve this situation. Of course, the first step was to acknowledge the entire problem of female empowerment could not be addressed by any one group. Women need political representation, they need to move up the corporate ladder, and they need a safe and secure environment when they travel. These are larger issues that need interventions from the state and the government. But we concluded that focusing on small changes in the way primary education is imparted could bring the greatest return on investment.

This is what resulted in the creation of the E&H Foundation, which aims to give quality education to girls in the 6 to 10 age group. A number of studies show that this is the cohort that is the most curious, that learns the fastest, that retains knowledge, and that uses this education to do well in life. A girl with quality primary education is healthier, more socially conscious, and more assertive and confident than her counterpart who might be wealthier, better located, or better taken care of, but who did not get quality primary education.

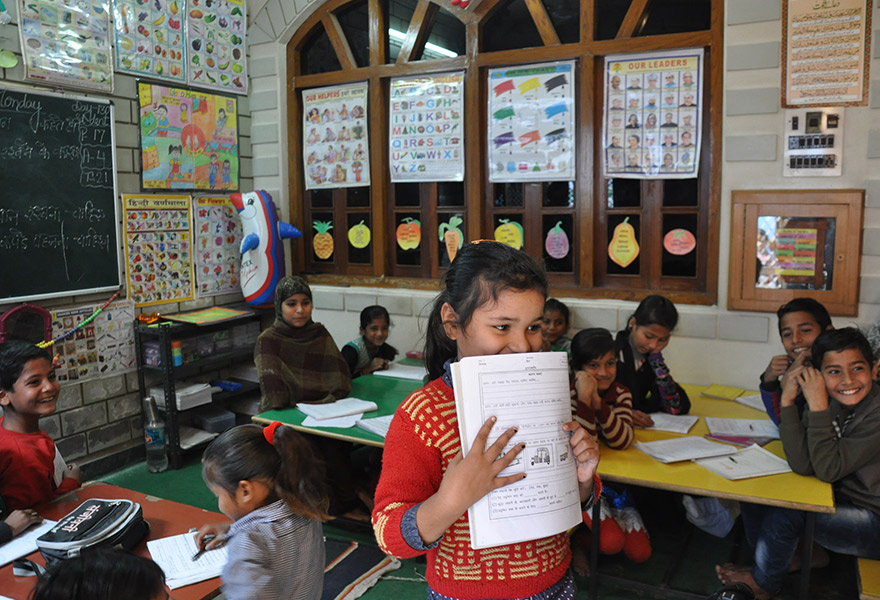

That is what motivated us to make small changes in how education is imparted. We selected a geography that is particularly distressed. Large parts of northern India suffer from acute patriarchy, adult illiteracy, and abysmal infrastructure. In the state of Uttar Pradesh alone, nearly 20 million school-going children suffer poor quality teaching, resulting in below average learning indicators. Here we decided to intervene and try out some simple solutions that would not only alter the learning environment but also keep costs low to allow us to scale up.

We were enormously helped by the fact that a former professor had come up with a working model, appropriately titled Gyan Shaala, meaning “Knowledge Provider.” The classroom is brought close to where the children live, the teacher is trained in child-friendly pedagogy, learning is gradual and closely monitored, and attendance is incentivized. Technology enables remote access, measurement of impact, and constant improvement. As a result, all the problems that we identified get tackled through a supervision mechanism that builds into a feedback loop and allows dynamic corrections.

This way we can provide quality education to more than 10,000 children from poor homes, where education has remained a dream for too long. We see quick results. These young girls are definitely more confident. Coming to our classes is easy, as they are housed right in the neighborhood and not far away where they fear to travel. Daily worksheets provide incremental learning and assessment instead of suffering from the overload that year-end examinations tend to impose. Parents are happy as their children are within shouting distance and well taken care of.

The challenge and the hope

All this comes at a cost though. The program works out to $50 dollars per student per year, despite the large scale. This money must be raised, as none of our children can pay for their education. Replicating this model, even in another language medium in another state, is easy, as the template is simple and well-designed. However, developing content and training teachers requires money and investment in research. Because the state is wary and continues to look at our intervention with suspicion, it will not fund such a program and would even shut it down if given the opportunity.

That is why this pilot program is such a great experience. It allows us to tackle a large-scale problem through simple steps and steady innovation. Our intervention produces results, both in the short and the long run. It requires resources, some that come easy and some that need relentless pursuit. New problems emerge, but a motivated workforce spends overtime finding solutions. These girls will demand better quality health care, more respect at home, improved governance in their village and city councils, and safer and cleaner workplaces. For a region that is emerging as a major economic powerhouse, empowering its children to seek high-quality education is key to continued growth and development.

Amir Ullah Khan is a development economist who teaches at the Indian School of Business and the Manipal Institute of Technology. He is advisor to the Government of Telangana and has previously worked with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the India Development Foundation, and Encyclopedia Britannica.

Dr. Amir Ullah Khan, PhD

Development Economist

Indian School of Business

Manipal Institute of Technology