e will be the first generation to leave our children the legacy of a world that is in worse shape than when we were born. That’s a pretty daunting statement, but I’m afraid it’s true. And, if you read the reports being released by a wide range of expert climatologists, it is a pretty dire situation.

Not one to be discouraged by what seems like an unsurmountable mountain to climb, I have chosen to focus on one aspect of climate change that I feel is manageable: food security.

A changing climate will lead to food scarcity and price increases. It will lead to changes in where and how food is raised. It will also lead to access issues for the most vulnerable populations. And yet, nearly one third of the food we currently produce is wasted. ONE THIRD! If wasted food were a country, it would be the third largest producer of carbon dioxide in the world, behind the United States and China.

If I told you we could all help solve world hunger by reducing the amount of food we waste, you would probably want to get involved. Well, it seems to be true. According to United Nations (U.N.) research, recovering just a quarter of wasted food could effectively end world hunger. As part of its Global Goals for Sustainable Development Initiative, the U.N. is working to cut food waste in half by 2030.

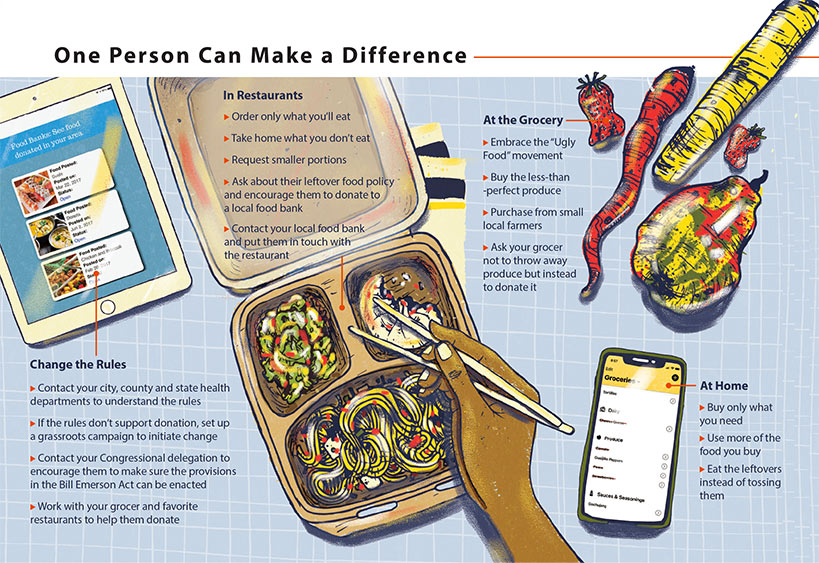

Like many things, this problem is larger and more preventable in the United States, where each American wastes an average of a pound of food each day! That fact alone made me think about what I could do personally to reduce food waste and help feed those in need. Here are some easy changes I’ve made in my own home:

- Buy only what I know we’ll eat and make sure we eat it

- If something has a bruise, eat around it

- Save leftovers for the next day’s lunch

My younger brother operates a small farm where he grows wonderful produce. But some of it’s also kind of ugly. It still tastes the same or even better because it’s fresher. There’s really nothing better than sweet peas (or any produce) eaten in the garden. It’s just not as pretty. I don’t care. I’m telling my friends not to care either. What am I doing that you can do too?

- Buy “ugly” produce

- Ask others to donate less than perfect food instead of tossing it

- Buy from local farmers

- Order the size you need

- If there are “sides” you don’t want, ask that they not be served

- Ask for a to-go box for what you don’t eat

- Find out about their leftover food policy and encourage them to donate it to a local group, or call your favorite local nonprofit to suggest they contact the restaurant to collect the leftovers

In talking with several friends who own restaurants, I was impressed. “We use the product,” they told me. “If we have leftovers, we use them in family meals for the staff that night or the next day.” “We try really hard to use up any leftovers. We keep waste logs and discuss waste so we can try to eliminate it.”

Education and advocacy are critical to seeing widespread change. This article is, frankly, my start at educating a broader audience. It’s also a call for advocacy. Join me in calling for change:

- Ask your grocery store manager what happens to less than perfect food. Follow the lead and make sure it doesn’t go to the landfills.

- When you’re in a restaurant, ask the same question. Then, find a local nonprofit that can go pick up the leftovers. Connect the two.

- Learn what’s happening in your local area to try to reduce food waste. Groups like Food Shift in California’s Bay Area and the James Beard’s Waste Not program are leading the way. Even the EPA has a toolkit for reducing waste.

- Learn about local food laws that prohibit safe food donations. Start a grassroots effort to change the laws.

- Ask your congressional delegation to make sure local red tape doesn’t get in the way of the Bill Emerson Act. Request they pass laws like the French did to reduce food waste but for restaurants, too.

Mary Deming Barber, APR, Fellow PRSA, is president of Food PR & Communications, a food-focused strategic communications consultancy. During her 40-year career, she has led award-winning programs for a wide range of food commodity boards, international brands and restaurants while employed by agencies and as an entrepreneur. She thrives on spotting trends that fit client goals and turning those into programs that are as leading-edge as they are successful.

Barber is well known nationally for her leadership and service in the International Foodservice Editorial Council and the Public Relations Society of America.

She loves to eat anything picked and eaten immediately in a farmer’s field — corn barely boiled so the sugar hasn’t turned yet

Mary Deming Barber, APR, Fellow PRSA, is president of Food PR & Communications, a food-focused strategic communications consultancy. During her 40-year career, she has led award-winning programs for a wide range of food commodity boards, international brands and restaurants while employed by agencies and as an entrepreneur. She thrives on spotting trends that fit client goals and turning those into programs that are as leading-edge as they are successful.

Barber is well known nationally for her leadership and service in the International Foodservice Editorial Council and the Public Relations Society of America.

She loves to eat anything picked and eaten immediately in a farmer’s field — corn barely boiled so the sugar hasn’t turned yet